The following was triggered by "A Man for All Markets: From Las Vegas to Wall Street, How I Beat the Dealer and the Market". The book is super fun, very similar to “You are Surely Joking, Mr Feynman” if you read that.

It is also based on constant experience where group decision making are annoying. Usually, these are joint trips. I tend to want to make decisions (i.e. define the date, book the hotel, book the plane) as fast as possible. My argument is that most things don’t really matter as long as the people are fun. If the people are not fun than the best AirBnB in the world does not change shit.

That's somewhat uncorrelated but still a trigger for this piece.

All this is obviously not my own thinking but a re-cap of what I read somewhere else. The primary texts are below. I have not read those but a mixture of Wikipedia and what I found online.

- Rational choice and the structure of the environment (Herbert A. Simon)

- The Mating Mind (Geoffrey Miller)

Decision Making Types

There are two types of decision maker.

Scenario:

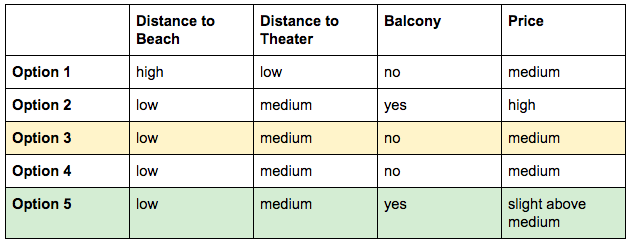

We are looking at a an apartment for a short trip. The factors are simple: how far is to the beach and to the Theater. Plus the some apartments are nicer than others, the placeholder for this here is a balcony to make it binary. The price ranks from low to high.

These are the options:

Satisficer:

The Satisficer defines a basic criteria and takes the first options that meets the criteria. So if the criteria here is to be close to the beach and pay a medium price, he/she would take option 3 and stop evaluating and get on with life.

That saves time but leads to the satisficer missing option 5 which is the same as option 3 but has a balcony. Yet - crucially - the search costs are higher for the satisficer than the benefit a balcony brings.

Maximizer:

The maximizer also starts with a baseline. Say, the criteria are the same as above, so distance to beach = medium or low, price = medium or low.

Once these criteria are fulfilled, the maximiser continues to maximise utility. So trying to take the get the best value for money. That has the issue that the options in the real world are nearly endless which in essence means that the only limit is the time spend in generating alternative options. That leads to unhappiness for Maximizers in general as the best value option cannot actually be obtained.

Extremely expensive ketchup for maximizer

Other than the cool word “satisficer” and that one can recognise people who fall in either category it is not obvious what the benefit of this concept is.

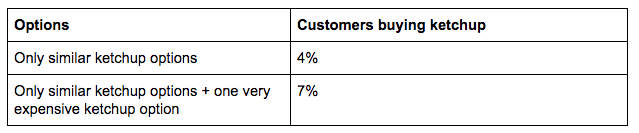

One story of how the concept is operationalised is very expensive ketchup. The suggestion is that supermarkets should add an obviously expensive version of a product in each category. A maximiser consumer considering different choices of ketchups with marginally different prices will not be able to make a decision because the time to choose would be too long.

But, as soon as there is a very expensive option the consumer is happy by “not taking that product”. Relative to the expansive option all the other options are good and hence the consumer can make a decision and be happy about them.

The point of the expensive option is not up-selling or a higher price. The presence of that option is entirely to increase the absolut sales of the the other options compared to a baseline without the expensive option.

I have no idea if this story is true, but it certainly sounds cool and it might as well be true.

The 37% Rule

This is also expressed in something called the secretary problem, the marriage problem or a variety of other names.

The set-up is this: you have n applicants. You interview them sequentially. You take a decision after each interview and cannot change it. Other key assumptions: having interviewed people you can judge the quality perfectly. The decision to accept or reject compares the quality of the current candidate to the past ones but ignores future ones.

The goal is to maximise the priority of selecting the best candidate. Since you cannot go back and accept rejected candidates and you can only “accept” a candidate who is better than the past the question is when to stop looking for a better candidate and take the next one who is better than all the ones before.

The answer is crazy: take the candidate qualified for acceptance (i.e. better than the previous) after n/e. At “reasonable” numbers 1/e which is 37%.

In other words: estimate your pipeline of candidates. Start interviewing. Stop at the best candidate after 37%.

(It is amazing that e would express itself here - I don't know enough about e to thing about this today)